This blog created for educational purpose under the subject EDG 4008 (CROSS-CULTURAL COUNSELLING). Let's explore together!!

Religion in Germany

As

one may expect from a country with 1300 years of Christian tradition,

Christianity is still the predominant religion in Germany. Although the number

of practicing Christians is on the decline, the Christian religion in Germany

is present in the country’s cultural heritage.

RELIGION IN GERMANY – CHRISTIANITY

About

65% to 70% of the population are followers of the Christian religion in

Germany. They are more or less evenly split between the mainstream

denominations of Lutheran-Protestantism and Calvinism united in the EKD (Evangelical

Church in Germany) and the Roman Catholic Church. Due to the historical

development of religion in Germany, these denominations are concentrated in

specific regions.

In

the course of the Protestant Reformation and the ensuing Thirty Years’ War in

the 15th and 16thcenturies, religion in Germany ended up being distributed

according to the preferences of local rulers: Therefore, most areas in the

South or West (especially Bavaria and Northrhine-Westphalia) are Catholic while

the North and East are mainly Protestant. However, the Communist regime of the

former DDR (German Democratic Republic) frowned upon religion in

Germany’s eastern parts until the reunification in 1990. This explains why the

percentage of self-confessed atheists is particularly high in these federal

states.

Other

strands of Christian religion in Germany are the so-called Free Evangelical

Churches, a loose union of congregations adhering to Baptism, Methodism and

related faiths such as the Mennonites, as well as the two Orthodox churches.

Christian evangelism in Germany goes back to U.S. American missionary efforts

in the 19th century. Both the Greek-Orthodox and the Russian-Orthodox

religion in Germany became established here with the Greek and Serbian

immigrant population in the 1960s and 1970s.

RELIGION IN GERMANY – MINORITY RELIGIONS

Apart

from these smaller Christian congregations, important minority religions in

Germany are Islam (about 4 % of the German population), Judaism, and Buddhism

(both of which represent less than 1% of Germany’s inhabitants).

Judaism

The atrocities

of the Holocaust are overshadowing the history of Judaism in Germany.

According to sources from late Antiquity, Jews have been living in Germany

since 321 AD. For more than one and a half millennia, the relationship between

the Jewish Diaspora and Germany’s majority population vacillated between quiet

coexistence and religiously motivated persecution, between the Jews’ status as

social outcasts and their slow assimilation into mainstream society. Before

1933, there were more than 600,000 Jews in Germany. During the following twelve

years, the viciously anti-Semitic Nazi regime killed most of those who didn’t

emigrate.

Today,

more than 65 years after the end of World War Two, the Jewish community in

Germany counts over 100,000 members. The increase in numbers is also due to

Jewish immigration from the former Soviet Union. The majority of German Jews

(the more observant and conservative ones) feel represented by the Central

Council of Jews in Germany, while about 3,000 liberal Jews belong to the much

smaller Union of Progressive Jews in Germany.

Islam

In

direct comparison with Judaism, Islam is a far more recent religion in Germany.

It goes back to the post-World War Two immigration of so-called Gastarbeiter (foreign

workers) and refugees. Most Muslims in Germany have a Turkish, Kurdish,

Iranian, Palestinian, or Bosnian background, and they have organized themselves

in a diverse range of decentralized organizations. These include, for example,

the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs, supported by the Turkish

government and representative of Sunnite Islam in Turkey; the AABF, an umbrella

organization for Alevites from Kurdish regions; the association of Bosnian

Muslims, and many others.

Religion and Morality in Eastern Germany

The

geographical idiom ‘eastern Germany’ today refers to a wide range of issues. As

a region, it is part of Germany, and is situated at the heart of Europe. At the

same time it is still remembered in both East and West as having belonged to

the socialist East. It has been considered as opposed to the capitalist West,

from which point of view it belonged to the historically excluded part of

Europe. Furthermore, the region that once constituted a country in itself is

generally depicted as one of the most secular societies of Europe – after the

political Wende, no revival of traditional or “new” religiosity was registered,

as has been the case elsewhere.

However, the emergence of the secular in eastern Germany is very specific and linked to its main distinctive features – Protestantism on one hand and socialism on the other. Much has been written on religion in this region from a quantitative-sociological, historical or theological-institutional point of view, but little is known about actual practice today. This project will undertake the study of religion in eastern Germany from ethnographic perspectives.

NARRATIVES OF SECULARIZATION

Both

the concepts of the secular and of secularisation have been subject to major

criticism in the past decades. Nevertheless, secularisation has remained the

dominant paradigm for studying and analysing religious change in eastern

Germany. At least three major scientific narratives of religious decline in

this particular region can be distinguished in this argument.

1. One narrative of secularisation stresses the governmental

policies of the past – the Nazi-Regime on one hand and on the other hand “real

existing communism”. From this perspective, in East Germany the atheist policy

of the communist regime was most successful.

2. Functionalist-oriented narratives stress that in the GDR,

in particular in its final years, the churches were part of the opposition and

that after the fall of communism they could no longer play this role, resulting

in turn in the decline of religious participation.

3. A further narrative indicates that in eastern Germany

secularisation set in much earlier, well before the political divide into East

and West, that is, probably with the Enlightenment and that it was therefore

not only the result of communist policy. This long-term perspective follows a

Weberian approach to secularisation with its underlying assumption that the

more ‘modern’ a society is, the more ‘secular’ it will be.

Social

scientists observing the changes in church membership, church attendance and

beliefs and practices of a religious character in eastern Germany after the

Second World War have demonstrated that there is a general decline in religious

interest and involvement. During 40 years of socialism church membership

declined from about 90 to about 30 percent. Since the end of socialism there

has been no significant change in membership or attendance. While western

Germany has also been affected by secularisation processes, this tendency here

is much weaker and church membership is much higher, 84.4 percent in 1998. The

major change that took place in the Protestant and Catholic churches in eastern

Germany after Unification was probably a political one, that is, that they were

re-established as public bodies receiving public funding. Still, those persons

who are in some way engaged in religion or church life do so as a minority with

all the implications this involves (‘wider den Strom’). The secular is thus an

inevitable part of any research project on religion and its meanings and practices

in eastern Germany. It cannot be assumed that religion is the dominant source

of morality. The study of religion must necessarily be linked to considerations

of the legal and demographic status of religious communities and institutions.

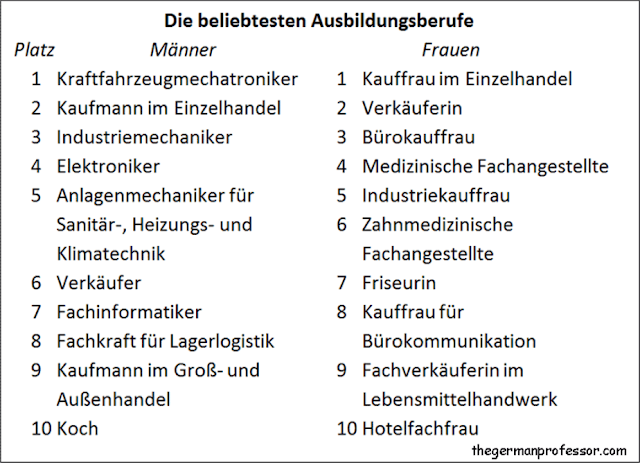

Top 10 career paths in Germany

These are the latest statistics of the German Federal Statistics

Office (Statistisches

Bundesamt) on the most popular career paths among young Germans

and compiled them into two charts.

The first

chart shows the most popular majors at Germany’s universities. Students

graduating from secondary school may study at a university if they fulfill

entrance requirements and pass the qualifying school-leaving exam (Abitur).

About 30% of secondary school graduates qualify for and choose this path.

The second

chart shows the most popular choices among Germany’s 345 officially recognized

career training programs (Ausbildungsberufe). The

remaining 70% of secondary school graduates participate in Germany’s duales

System or dual system of education, in which trainees

attend a vocational school (Berufsschule) part-time while

also gaining practical experience through on-the-job training.

Both lists are broken down by gender, which can offer some basis

for further discussion in the classroom. Some reading and interpretation

questions for students follow each chart.

1st Chart

2nd Chart

A guide to psychotherapy in Germany: Where can I find help?

Most people find it easy to find the right

doctor when they have a physical illness. But a lot of people do not know who

to turn to if they have mental problems or illnesses. People are also often

reluctant to talk about mental illnesses. We have put together some information

to help you find your way through the health care maze. It presents the

various treatment options, explains who is the right person to

talk to in different situations, and answers practical questions that may arise

if psychotherapy seems like it might be a good idea.

Who can

I turn to first if I have mental health problems?

Many people turn to their friends and family

first if they don't feel well. People who need professional help for

psychological problems can first talk to their family doctor, a psychosocial

counselor or go straight to a psychotherapist or psychiatrist. In an emergency

there are also psychiatric practices with emergency services as well as

psychiatric clinics.

Psychosocial counseling centers offer help

for a variety of issues, including family, women, childcare and addiction. The

staff at such centers have different professional backgrounds. You might find,

for example, doctors, social workers (in German:Sozialpädagogen and Sozialarbeiter),

psychologists, psychotherapists, as well as specially trained care workers all

working together to help people solve their problems. The counseling centers

are usually funded by supporting organizations, subsidies and donations. They

do not offer therapy themselves, but they can offer advice,

information about support options, and initiate contact.

Social psychiatric services are another point

of contact. In Germany they are run by local health authorities and can be used

for free by everybody. They particularly support people who need treatment for acute or chronic mental illnesses. The social psychiatric service

teams are also made up of doctors, care workers, psychotherapists and social

workers. The centers generally do not offer therapy themselves but can determine whether somebody

requires treatment. They also offer extra support to people who are currently

in therapy or have recently been in a clinic. Family, friends and colleagues

can also contact the social psychiatric service if they have the feeling that

somebody they know needs help. Where necessary the social psychiatric services

also offer home visits.

Just like therapists, the staff at the social

psychiatric services and psychosocial counseling centers are obliged to

maintain patient confidentiality.

What is

psychotherapy and when is it an option?

When people hear the word "psychotherapy" they might think of somebody lying on a

couch talking about their childhood while the therapist is sitting in the chair

next to them listening. This is a common image that we see of psychotherapy in

films and other media. But there are lots of different kinds of psychotherapy

that use very different approaches. The most commonly used methods are

cognitive behavioral therapy and depth psychology therapy.

The goal of all psychotherapies is to relieve the symptoms caused by the

mental illness and improve quality of life. The question as to which method is

suitable depends on many aspects, including the type of problem or illness as

well as the preferences and personal goals of the person who needs therapy.

The most common mental illnesses and

disorders that are treated with psychotherapy include anxiety disorders, depression and addiction. By the way, psychotherapy is

not just used to treat mental conditions: It is also an option for people who

are dealing with chronic physical illnesses. Psychotherapists can also

refuse to provide treatment if they believe that there is no need for therapy, or if psychotherapy does not seem appropriate.

Psychologists,

psychiatrists and psychotherapists - who is who?

There are various professional titles in the

area of psychotherapy in Germany, and they can be quite

confusing. For example, many people think that psychologists and

psychotherapists are the same thing. But just because somebody has a degree in

psychology does not mean that they can automatically offer therapy. To be able to do so psychologists first have to

complete several years of practical psychotherapy training and then pass a

state examination.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)