This blog created for educational purpose under the subject EDG 4008 (CROSS-CULTURAL COUNSELLING). Let's explore together!!

Religion in Germany

As

one may expect from a country with 1300 years of Christian tradition,

Christianity is still the predominant religion in Germany. Although the number

of practicing Christians is on the decline, the Christian religion in Germany

is present in the country’s cultural heritage.

RELIGION IN GERMANY – CHRISTIANITY

About

65% to 70% of the population are followers of the Christian religion in

Germany. They are more or less evenly split between the mainstream

denominations of Lutheran-Protestantism and Calvinism united in the EKD (Evangelical

Church in Germany) and the Roman Catholic Church. Due to the historical

development of religion in Germany, these denominations are concentrated in

specific regions.

In

the course of the Protestant Reformation and the ensuing Thirty Years’ War in

the 15th and 16thcenturies, religion in Germany ended up being distributed

according to the preferences of local rulers: Therefore, most areas in the

South or West (especially Bavaria and Northrhine-Westphalia) are Catholic while

the North and East are mainly Protestant. However, the Communist regime of the

former DDR (German Democratic Republic) frowned upon religion in

Germany’s eastern parts until the reunification in 1990. This explains why the

percentage of self-confessed atheists is particularly high in these federal

states.

Other

strands of Christian religion in Germany are the so-called Free Evangelical

Churches, a loose union of congregations adhering to Baptism, Methodism and

related faiths such as the Mennonites, as well as the two Orthodox churches.

Christian evangelism in Germany goes back to U.S. American missionary efforts

in the 19th century. Both the Greek-Orthodox and the Russian-Orthodox

religion in Germany became established here with the Greek and Serbian

immigrant population in the 1960s and 1970s.

RELIGION IN GERMANY – MINORITY RELIGIONS

Apart

from these smaller Christian congregations, important minority religions in

Germany are Islam (about 4 % of the German population), Judaism, and Buddhism

(both of which represent less than 1% of Germany’s inhabitants).

Judaism

The atrocities

of the Holocaust are overshadowing the history of Judaism in Germany.

According to sources from late Antiquity, Jews have been living in Germany

since 321 AD. For more than one and a half millennia, the relationship between

the Jewish Diaspora and Germany’s majority population vacillated between quiet

coexistence and religiously motivated persecution, between the Jews’ status as

social outcasts and their slow assimilation into mainstream society. Before

1933, there were more than 600,000 Jews in Germany. During the following twelve

years, the viciously anti-Semitic Nazi regime killed most of those who didn’t

emigrate.

Today,

more than 65 years after the end of World War Two, the Jewish community in

Germany counts over 100,000 members. The increase in numbers is also due to

Jewish immigration from the former Soviet Union. The majority of German Jews

(the more observant and conservative ones) feel represented by the Central

Council of Jews in Germany, while about 3,000 liberal Jews belong to the much

smaller Union of Progressive Jews in Germany.

Islam

In

direct comparison with Judaism, Islam is a far more recent religion in Germany.

It goes back to the post-World War Two immigration of so-called Gastarbeiter (foreign

workers) and refugees. Most Muslims in Germany have a Turkish, Kurdish,

Iranian, Palestinian, or Bosnian background, and they have organized themselves

in a diverse range of decentralized organizations. These include, for example,

the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs, supported by the Turkish

government and representative of Sunnite Islam in Turkey; the AABF, an umbrella

organization for Alevites from Kurdish regions; the association of Bosnian

Muslims, and many others.

Religion and Morality in Eastern Germany

The

geographical idiom ‘eastern Germany’ today refers to a wide range of issues. As

a region, it is part of Germany, and is situated at the heart of Europe. At the

same time it is still remembered in both East and West as having belonged to

the socialist East. It has been considered as opposed to the capitalist West,

from which point of view it belonged to the historically excluded part of

Europe. Furthermore, the region that once constituted a country in itself is

generally depicted as one of the most secular societies of Europe – after the

political Wende, no revival of traditional or “new” religiosity was registered,

as has been the case elsewhere.

However, the emergence of the secular in eastern Germany is very specific and linked to its main distinctive features – Protestantism on one hand and socialism on the other. Much has been written on religion in this region from a quantitative-sociological, historical or theological-institutional point of view, but little is known about actual practice today. This project will undertake the study of religion in eastern Germany from ethnographic perspectives.

NARRATIVES OF SECULARIZATION

Both

the concepts of the secular and of secularisation have been subject to major

criticism in the past decades. Nevertheless, secularisation has remained the

dominant paradigm for studying and analysing religious change in eastern

Germany. At least three major scientific narratives of religious decline in

this particular region can be distinguished in this argument.

1. One narrative of secularisation stresses the governmental

policies of the past – the Nazi-Regime on one hand and on the other hand “real

existing communism”. From this perspective, in East Germany the atheist policy

of the communist regime was most successful.

2. Functionalist-oriented narratives stress that in the GDR,

in particular in its final years, the churches were part of the opposition and

that after the fall of communism they could no longer play this role, resulting

in turn in the decline of religious participation.

3. A further narrative indicates that in eastern Germany

secularisation set in much earlier, well before the political divide into East

and West, that is, probably with the Enlightenment and that it was therefore

not only the result of communist policy. This long-term perspective follows a

Weberian approach to secularisation with its underlying assumption that the

more ‘modern’ a society is, the more ‘secular’ it will be.

Social

scientists observing the changes in church membership, church attendance and

beliefs and practices of a religious character in eastern Germany after the

Second World War have demonstrated that there is a general decline in religious

interest and involvement. During 40 years of socialism church membership

declined from about 90 to about 30 percent. Since the end of socialism there

has been no significant change in membership or attendance. While western

Germany has also been affected by secularisation processes, this tendency here

is much weaker and church membership is much higher, 84.4 percent in 1998. The

major change that took place in the Protestant and Catholic churches in eastern

Germany after Unification was probably a political one, that is, that they were

re-established as public bodies receiving public funding. Still, those persons

who are in some way engaged in religion or church life do so as a minority with

all the implications this involves (‘wider den Strom’). The secular is thus an

inevitable part of any research project on religion and its meanings and practices

in eastern Germany. It cannot be assumed that religion is the dominant source

of morality. The study of religion must necessarily be linked to considerations

of the legal and demographic status of religious communities and institutions.

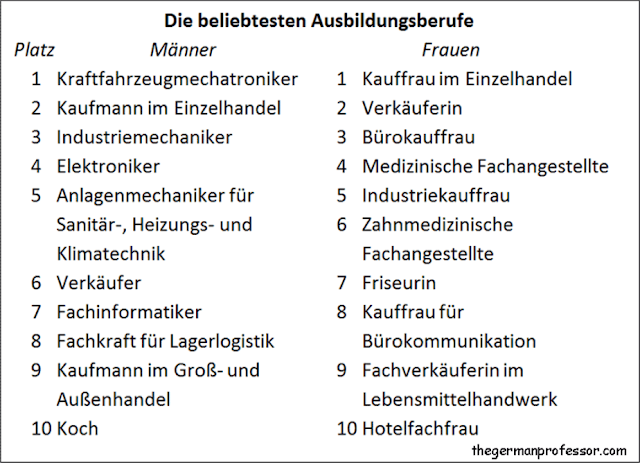

Top 10 career paths in Germany

These are the latest statistics of the German Federal Statistics

Office (Statistisches

Bundesamt) on the most popular career paths among young Germans

and compiled them into two charts.

The first

chart shows the most popular majors at Germany’s universities. Students

graduating from secondary school may study at a university if they fulfill

entrance requirements and pass the qualifying school-leaving exam (Abitur).

About 30% of secondary school graduates qualify for and choose this path.

The second

chart shows the most popular choices among Germany’s 345 officially recognized

career training programs (Ausbildungsberufe). The

remaining 70% of secondary school graduates participate in Germany’s duales

System or dual system of education, in which trainees

attend a vocational school (Berufsschule) part-time while

also gaining practical experience through on-the-job training.

Both lists are broken down by gender, which can offer some basis

for further discussion in the classroom. Some reading and interpretation

questions for students follow each chart.

1st Chart

2nd Chart

A guide to psychotherapy in Germany: Where can I find help?

Most people find it easy to find the right

doctor when they have a physical illness. But a lot of people do not know who

to turn to if they have mental problems or illnesses. People are also often

reluctant to talk about mental illnesses. We have put together some information

to help you find your way through the health care maze. It presents the

various treatment options, explains who is the right person to

talk to in different situations, and answers practical questions that may arise

if psychotherapy seems like it might be a good idea.

Who can

I turn to first if I have mental health problems?

Many people turn to their friends and family

first if they don't feel well. People who need professional help for

psychological problems can first talk to their family doctor, a psychosocial

counselor or go straight to a psychotherapist or psychiatrist. In an emergency

there are also psychiatric practices with emergency services as well as

psychiatric clinics.

Psychosocial counseling centers offer help

for a variety of issues, including family, women, childcare and addiction. The

staff at such centers have different professional backgrounds. You might find,

for example, doctors, social workers (in German:Sozialpädagogen and Sozialarbeiter),

psychologists, psychotherapists, as well as specially trained care workers all

working together to help people solve their problems. The counseling centers

are usually funded by supporting organizations, subsidies and donations. They

do not offer therapy themselves, but they can offer advice,

information about support options, and initiate contact.

Social psychiatric services are another point

of contact. In Germany they are run by local health authorities and can be used

for free by everybody. They particularly support people who need treatment for acute or chronic mental illnesses. The social psychiatric service

teams are also made up of doctors, care workers, psychotherapists and social

workers. The centers generally do not offer therapy themselves but can determine whether somebody

requires treatment. They also offer extra support to people who are currently

in therapy or have recently been in a clinic. Family, friends and colleagues

can also contact the social psychiatric service if they have the feeling that

somebody they know needs help. Where necessary the social psychiatric services

also offer home visits.

Just like therapists, the staff at the social

psychiatric services and psychosocial counseling centers are obliged to

maintain patient confidentiality.

What is

psychotherapy and when is it an option?

When people hear the word "psychotherapy" they might think of somebody lying on a

couch talking about their childhood while the therapist is sitting in the chair

next to them listening. This is a common image that we see of psychotherapy in

films and other media. But there are lots of different kinds of psychotherapy

that use very different approaches. The most commonly used methods are

cognitive behavioral therapy and depth psychology therapy.

The goal of all psychotherapies is to relieve the symptoms caused by the

mental illness and improve quality of life. The question as to which method is

suitable depends on many aspects, including the type of problem or illness as

well as the preferences and personal goals of the person who needs therapy.

The most common mental illnesses and

disorders that are treated with psychotherapy include anxiety disorders, depression and addiction. By the way, psychotherapy is

not just used to treat mental conditions: It is also an option for people who

are dealing with chronic physical illnesses. Psychotherapists can also

refuse to provide treatment if they believe that there is no need for therapy, or if psychotherapy does not seem appropriate.

Psychologists,

psychiatrists and psychotherapists - who is who?

There are various professional titles in the

area of psychotherapy in Germany, and they can be quite

confusing. For example, many people think that psychologists and

psychotherapists are the same thing. But just because somebody has a degree in

psychology does not mean that they can automatically offer therapy. To be able to do so psychologists first have to

complete several years of practical psychotherapy training and then pass a

state examination.

3.0 Germany: Folk Music

German Folk Music

Germany has many unique regions with their own folk traditions of music and dance. Much of the 20th century saw German culture appropriated for the ruling powers (who fought "foreign" music at the same time).

In both East and West Germany, folk songs called "volkslieder" were taught to children; these were popular, sunny and optimistic, and had little relation to authentic German folk traditions. Inspired by American and English roots revivals, Germany underwent many of the same changes following the 1968 student revolution in West Germany, and new songs, featuring political activism and realistic joy, sadness and passion, were written and performed on the burgeoning folk scene. In East Germany, the same process did not begin until the mid-70s, where some folk musicians began incorporating revolutionary ideas in coded songs.

Festival des politischen Liedes - 1970

Popular folk songs included emigration songs from the 19th century, work songs and songs of apprentices, as well as democracy-oriented folk songs collected in the 1950s by Wolfgang Steinitz. Beginning in 1970, the Festival des politischen Liedes, an East German festival focusing on political songs, was held annually and organized (until 1980) by the FDJ (East German youth association). Musicians from up to thirty countries would participate, and, for many East Germans, it was the only exposure possible to foreign music. Among foreign musicians at the festival, some were quite renowned, including Inti-Illimani (Chile), Billy Bragg (England), Dick Gaughan (Scotland), Mercedes Sosa (Argentina) and Pete Seeger (United States), while German performers included, from both East and West, Oktoberklub, Wacholder and Hannes Wader

3.0 Counseling: Visit to ‘Muzium Orang Asli Gombak’

Cross-Cultural Trip to ‘Muzium Orang

Asli Gombak’

Orang Asli Museum History started in year 1987 at an old

wooden building which was the officioal residence of former Director of Orang

Asli Affairs Department (JHEOA). Later in year 1995 (end of 6th

Malaysian Plan) the JHEO official built a new brick museum at cost of RM

3.5million. It was completed and hand-over to the JHEOA on 19 June 1998. The

museum was officiated by the 11th Seri Paduka Baginda Yang Dipertuan

Agong, Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah Al-Haj ibni Almarhum Sultan Hisamuddin

Alam Shah Alhaj on 02 March 2000 and was known as the Orang Asli Museum.

Objectives:

- 1. To document the past of the Orang Asli as part of history.

- 2. To collect all objects and material significant to the culture and life of the Orang Asli from various tribes in Peninsular Malaysia for future generation.

- 3. As source of research, ancient customs and tradition.

What about them?

i) Considered

as to be part of natives of this country.

ii) Population

is approximately 171, 193 and they are divided into three main tribes which are

Negrito, Senoi and the Proto-Malays (Aboriginal Malays).

iii) Each

tribe divided into 6 smaller tribes and speak different dialect, apart from the

local Malay dialect

Negrito

|

Senoi

|

Melayu Asli

Proto-Malays

|

Kensiu

|

Temiar

|

Temuan

|

Kintaq

|

Semai

|

Semelai

|

Lanoh

|

Semoq Beri

|

Jakun

|

Jahai

|

Che Wong

|

Orang Kanaq

|

Mandriq

|

Jah Hut

|

Orang

Kuala

|

Bateq

|

Mah Meri

|

Orang Seletar

|

Wood Carving and Crafts

Wood carving and crafts are the

products of the Orang Asli creativity based on nature and their beliefs,

especially in weaving of mengkuang and pandan leaves, bamboo and cane. In wood

carving, all creation depend on imagination and dream that depict good or evil

forces which are related to their believes and lifestyle.

In my opinion, learn about history is important because it

allows us to understand our past, which in turn allows to understand our

present. If we want to know how and why our world is the way it is today, we

have to look to history for answers. People often say that “history repeats

itself,” but if we study the successes and failures of the past, we may,

ideally, be able to learn from our mistakes and avoid repeating them in the

future. Studying history can provide us with insight into our cultures of

origin as well as cultures with which we might be less familiar, thereby

increasing cross-cultural awareness and understanding.

Recipe: German Chocolate Cake

German Chocolate Cake

The

BEST homemade German Chocolate Cake with layers of coconut pecan frosting and chocolate

frosting. This cake is incredible!

The

BEST homemade German Chocolate Cake with layers of coconut pecan frosting and chocolate

frosting. This cake is incredible!

Course:

Dessert

Cuisine:

American

Servings:

15

Calories:

591 kcal

Author:

Lauren Allen

Ingredients

For the Chocolate Cake:

2

cups sugar

1-3/4

cups all-purpose flour

3/4

cup unsweetened cocoa powder

1

1/2 teaspoons baking powder

1

1/2 teaspoons baking soda

1

teaspoon salt

2

large eggs

1

cup buttermilk

1/2

cup oil , canola or vegetable

2

teaspoons vanilla extract

1

cup boiling water

For

the Coconut Frosting:

1/2

cup brown sugar

1/2

cup sugar

1/2

cup butter

3

egg yolks

3/4

cup evaporated milk

1

tablespoon vanilla extract

1

cup chopped Pecans

1

cup shredded coconut

For

the Chocolate Frosting:

1/2

cup butter

2/3

cup unsweetened cocoa powder

3

cups powdered sugar

1/3

cup evaporated milk

1

teaspoon vanilla extract

Instructions

1.

Heat oven to 375°F. Grease two 8 or 9-inch round baking pans. I like to cut a

round piece of wax or parchment paper for the bottom of the pan also, to make

sure the cake comes out easily.

For the Cake:

1.

Stir together sugar, flour, cocoa, baking powder, baking soda and salt in large

bowl. In a separate bowl combine the eggs, buttermilk, oil and vanilla and mix

well. Add the wet ingredients to the dry ingredients and mix to combine. Stir

in boiling water (batter will be very thin). Pour batter into prepared pans.

2.

Bake for 25 - 35 minutes (depending on your cake pan size. The 9'' pan takes

less time to bake) or until a toothpick inserted in center comes out clean or

with few crumbs. Cool 5 minutes in the pan and then invert onto wire racks to

cool completely.

For the coconut frosting:

1.

In a medium saucepan add brown sugar, granulated sugar, butter, egg yolks, and

evaporated milk. Stir to combine and bring the mixture to a low boil over

medium heat. Stir constantly for several minutes until the mixture begins to

thicken.

2.

Remove from heat and stir in vanilla, nuts and coconut. Allow to cool completely

before layering it on the cake.

For the Chocolate Frosting:

1.

Melt butter. Stir in cocoa powder. Alternately add powdered sugar and milk,

beating to spreading consistency.

Add

small amount additional milk, if needed to thin the frosting, or a little extra

powder, until you reach your desired consistency. Stir in vanilla.

Cake Assembly:

1.

Place one of the cake rounds on your serving stand or plate.

2.

Smooth a thin layer of chocolate frosting over the cake layer, and then spoon half

of the coconut frosting on top, spreading it into a smooth layer. Leave about

1/2 inch between the filling and edge of cake.

3.

Stack the second cake round on top. Smooth chocolate frosting over the entire

cake.

4.

Spoon remaining coconut frosting on top of the cake.

Recipe Notes

*If baking at

high altitude add 3 tablespoons extra flour.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)